Since 2013, the state’s leading transportation agencies have been planning a massive reconfiguration of Interstate 90, Soldiers Field Road and the Framingham/Worcester railroad line along the Charles River waterfront in Allston.

If and when the project is finished – potentially sometime in the early to mid-2030s – Allston will have new and upgraded bike and pedestrian connections to the Charles River, a new waterfront park, a new grid of local streets to set the stage for a huge new urban neighborhood, and a major new commuter rail station that could be directly connected to Kendall Square via the Grand Junction rail line.

It’s being called the “Allston Multimodal Project,” and over the next two years, it’s expected to go through a federal environmental review process that will determine many of the details of how the project gets built.

This is a story that StreetsblogMASS expects to cover in detail over the next few years, but on this page (which we’ll continue to update as new details become available), we’re providing a high-level overview to help people understand the broad outlines of what’s being proposed, and how advocates are hoping to improve the plans before it goes under construction for the better part of a decade.

Where is it happening?

The project area encompasses a 90-acre wedge of land that’s shaped like a stingray swimming towards Belmont. It’s about a mile south of Harvard Square, and about 3 miles to Government Center in downtown Boston:

What’s being proposed

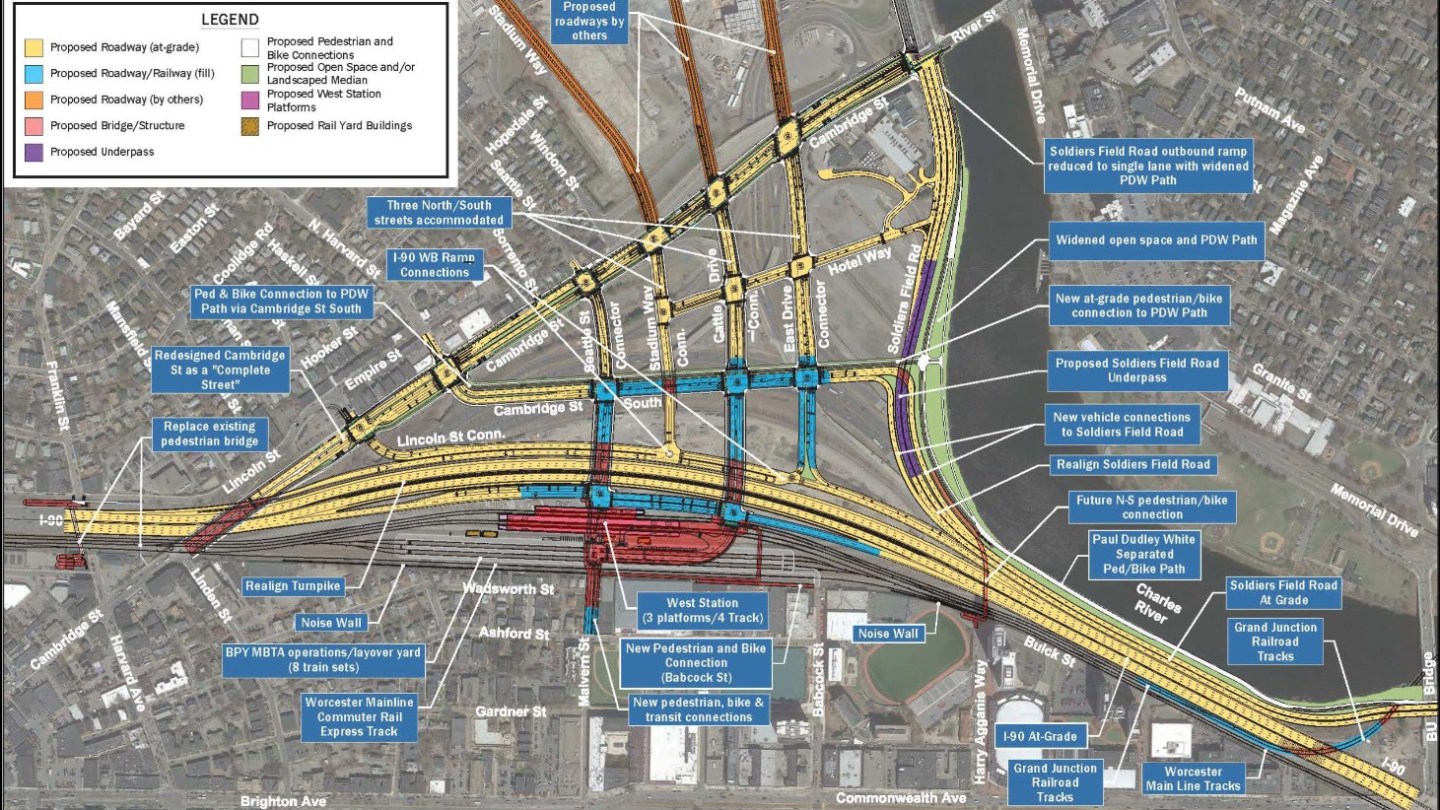

This design has evolved considerably since 2013 and is likely to evolve further in the next few years, but this map illustrates the project’s major elements as of May 2022:

The project’s proposed new bike and pedestrian accommodations, new streets and highways, and new transit facilities are outlined in slightly more detail below.

Why is MassDOT doing this?

In 2013, the private-sector freight railroad CSX vacated its railyards in the project area, which freed up 30 acres of land between the Turnpike and the commuter rail line.

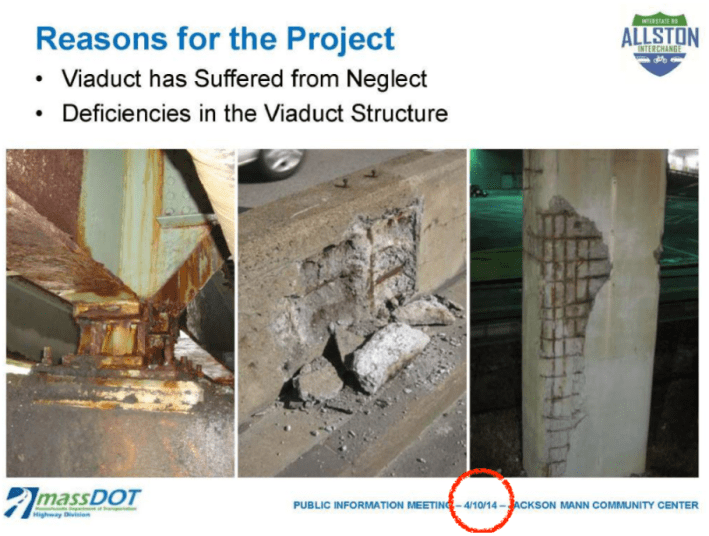

Around the same time, MassDOT started raising the alarm that the viaduct carrying I-90 through this area was in bad shape, and needed to be replaced (see the presentation slide below, from April 2014):

The transition to all-electronic tolling at the end of 2016 opened up additional opportunities. Until then, the state had been forced to maintain a maze of queuing lanes where traffic used to wait to go through the tolls; the new technology rendered many of those ramps unnecessary.

And underneath all of that unwanted transportation infrastructure lies 90 acres of extremely valuable real estate owned by Harvard University. They haven’t shared any specific plans, but the university is already expanding its campus along nearby Western Avenue, and its officials have talked about their ambitions to make the area the “next Kendall Square.”

Because they control the real estate, and also have considerable political and financial influence, Harvard’s real estate interests play a major role. The university has specified that the project will need to maximize the “technical feasibility and economic viability” for development on their land (read more on Harvard’s financial interests here in the “who’s going to pay for it?” section below).

Finally, the project opens up numerous opportunities to make better connections for bikes, pedestrians and transit users within and across the project area. Harvard wants a new commuter rail station as part of the project (more on that below) and a walkable grid of new city streets through their land; Allston neighbors see an opportunity to gain better access across the Turnpike and to the riverfront.

West Station and the Grand Junction

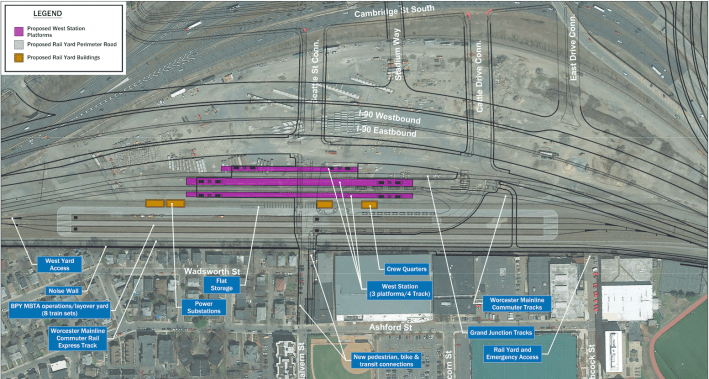

A new “West Station” would serve trains on the Framingham/Worcester commuter rail line, plus a potential new rail line to Kendall Square and North Station via the Grand Junction right-of-way.

The project would also build new dedicated rails for the Grand Junction line between West Station and the BU Bridge, and a bike, pedestrian, and transit-only roadway would connect the new station to Malvern Street, offering a short walk to the Packards Corner Green Line stop.

The design of West Station is still in flux; in April 2024, transit advocates won some major concessions to shrink the footprint of the station’s proposed track infrastructure, which could considerably simplify the project’s design.

To mitigate traffic, transit advocates and a number of elected officials would also like the state to improve commuter rail service on Framingham/Worcester line during the years when the Turnpike and Soldiers Field Road are being rebuilt.

TransitMatters has advocated for upgrading stations and electrifying the Framingham/Worcester line to allow for frequent, all-day regional rail service to move thousands of additional commuters who would otherwise drive on the Turnpike.

The Paul Dudley White Path and new bike/pedestrian connections

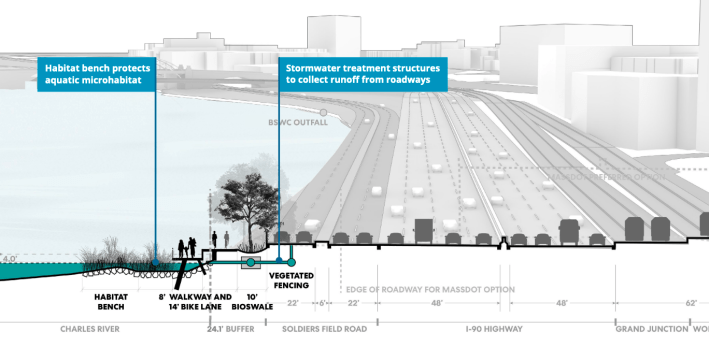

In many places through the project area, only a battered guardrail separates the Paul Dudley White waterfront bike and pedestrian path from the noise and pollution of Soldiers Field Road (both are maintained by the state’s Department of Conservation and Recreation).

By relocating Soldiers Field Road away from the waterfront, the Allston Multimodal Project could create considerably more space on the waterfront for bike and foot traffic, plus new parkland.

The current plan also includes another new separated bike path that will connect the site from east to west, a new Cambridge Street bridge with new crosswalks and protected bike lanes, a wider, ADA-accessible replacement for the Franklin Street pedestrian bridge over the Turnpike at the western edge of the site, a car-free transitway from West Station to Malvern Street and Packard’s Corner, and a new bike and pedestrian bridge over the Turnpike near the eastern end of the project, to connect Agannis Way to the Charles riverfront.

Stuffing 200,000 cars down ‘The Throat’

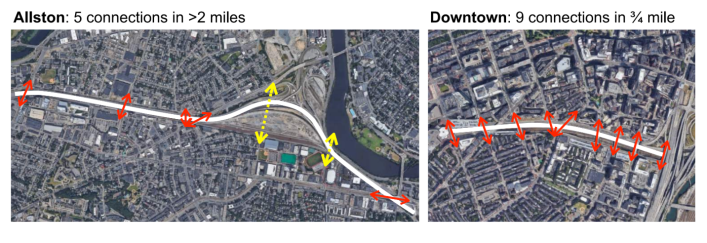

The most technically challenging part of the Allston Multimodal Project involves what planners are calling “the throat,” the area of the Charles River waterfront where the Turnpike, Soldiers Field Road, and two commuter rail tracks squeeze through a choke point next to the Charles River that’s just over 210 feet wide.

MassDOT has asserted that an eight-lane Turnpike is necessary to move the 147,000 vehicles that currently the Turnpike on an average day (the four-lane Soldiers Field Road carries an additional 66,000 vehicles per day).

Bear in mind, though, that the City of Boston has set a goal of cutting car traffic in half within the next decade to meet its climate goals, and traffic reduction is becoming an increasingly urgent priority for the state to meet the obligations of its own climate laws.

MassDOT has not explained how present-day traffic volumes are relevant for a project that won’t be finished until the 2030s.

Tearing down and rebuilding 12 lanes of highway on top of the banks of the Charles River, while also keeping traffic flowing, also presents a fiendishly difficult challenge for the contractors who will ultimately build the project.

At one point, MassDOT suggested building a “temporary” highway in the middle of the Charles River that would stand for several years while the new highways were built on the riverbank; at another point, MassDOT proposed simply rebuilding the existing Turnpike viaduct in the same location.

As of 2024, the current design embraces an “at-grade” option proposed by A Better City, a business group that was founded to influence the design of the Big Dig in the 1990s.

The “at grade” plan would put both highways and rail lines at the river’s level.

MassDOT is currently spending $86 million to rehab the Turnpike viaduct to keep it standing for a few more years.

“You can keep the elevated structure open to traffic while you build a new road underneath it. You don’t need to build a temporary viaduct or shift lanes, which saves a lot of time and money,” Rick Dimino, then the president of A Better City, told StreetsblogMASS in March 2023.

A 7-year construction project

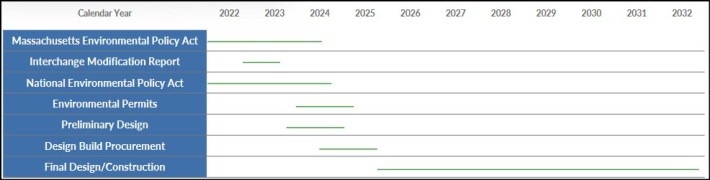

According to its May 2022 federal grant funding application, MassDOT expects to take 7 full years to complete the entire Allston/I-90 project.

MassDOT is prepared to reduce the Turnpike to a 6-lane cross-section for much of the 2020s, and has warned that the Framingham/Worcester line could also be reduced to a single track through the “throat” section for extended periods of time.

Transit advocates worry that closing a track will constrain the MBTA’s ability to add more train service when the need for better transit alternatives will be most acute.

After it finally reached a consensus around the at-grade alternative for the “throat” section, the project will began a detailed environmental review under the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires MassDOT to analyze the project’s impacts (including the construction impacts) with a detailed “environmental impact statement.”

That two-year process kicked off in August 2022, after MassDOT submitted a “notice of project change” to reflect the updated conceptual design.

This will also be the time when MassDOT would be required to file for state and federal permits to build along the banks of the Charles River, which will be a probable point of contention from environmental groups.

The current 12-lane highway design would require MassDOT to fill and pave over the banks of the Charles River in parts of the space-constrained “throat” segment.

Who’s going to pay for it?

According to a May 2022 federal grant application, MassDOT expects to spend roughly $2 billion for all of the project’s components (note that this figure is not adjusted for inflation, which has been considerable in recent years).

As of spring 2024, the Commonwealth has scraped together nearly $1.8 billion in pledges, including:

- A $335 million Reconnecting Communities grant from the federal government (MassDOT had originally requested $500 million in funding from this program)

- $920 million from state taxpayers, consisting of $470 million in new state debt (which will need to be repaid with interest) and $450 million from the Fair Share Amendment’s Education and Transportation Fund;

- $200 million from Turnpike tolls;

- A $100 million commitment from the City of Boston for the project’s street infrastructure;

- An additional $100 million from City of Boston “value capture” funds – i.e., leveraging the anticipated new property tax revenue from Harvard’s 90-acre real estate development;

- $90 million from Harvard, plus $10 million from Boston University, to build West Station

Harvard’s commitments are noteworthy: the institution has a $49 billion endowment, and stands to make a killing on real estate development when the project’s infrastructure is finally built.

But their proposed contribution amounts to about 5 percent of the project’s total price tag.

The Commonwealth’s taxpayers have already been generous to Harvard where this property is concerned: the University bought this land from the state in 2003, when the board of the former Massachusetts Turnpike Authority voted to sell these 90 acres to Harvard for just $75 million, which is about $130 million in 2024 dollars.

For comparison’s sake, a 1/3rd-acre parking lot on Newbury Street recently sold for $40 million.

What advocates are watching

Bike, pedestrian and transit advocates stress that there’s a lot to like about the Allston Multimodal project. A public “task force” of several dozen stakeholders has been meeting regularly and has already managed to improve the state’s proposal in significant ways.

But there are still some unresolved issues that advocates are watching as the project converges on a final design, including:

- Can the project’s massive highways be value-engineered to better align the project with the state’s ambitious climate and traffic reduction goals?

- How will the state improve regional transit service to mitigate traffic hassles during the 7-year construction period?

- Will MassDOT be allowed to encroach on the present-day banks of the Charles River under state and federal environmental protection laws?

- How will bike and pedestrian access be maintained on Cambridge Street and the Paul Dudley White paths during each phase of construction?

- Will the new city streets proposed north of West Station really have 4- or 5-lane cross-sections, even though multi-lane streets have well-documented safety problems, especially for pedestrians?

- Who’s really going to pay for all this – and will it saddle the cash-strapped MBTA with even more debt that it can’t afford?

Through the environmental review process, though, the agency will soon need to nail down these details and many others. We plan to cover this project closely, and will update this page as new information becomes available.

Read more detailed coverage of the Allston I-90 project in our archives.

Editor’s note: this is a rewritten version of an article we’ve been revising since 2019 to reflect changes in the project. You can read an archived version of the 2022 revision, which contains additional detail about the development of the “at grade” highway design, here.