“The kids are not okay.”

That was the eye-opening message delivered by Mayor Wu and a group of city and state education leaders on Wednesday during an announcement at Dorchester’s Joseph Lee K-8 School on Talbot Avenue. The mayor said her administration will commit $21 million to fund programs aimed at addressing what leaders described as a “mental health crisis” in the city’s youth population, spurred in part by the impacts of the Covid pandemic.

The Lee School is one of several city schools that will participate in a “Children’s Wellness Initiative” and another program, “Trauma-informed School System Transformation.”

Other neighborhood schools that will be included are BCLA McCormack 7-12, Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary School, Madison Park Technical and Vocational High School, the Murphy K-8 School, TechBoston Academy, the Henderson K-12 Inclusion School, and Young Achievers School in Mattapan.

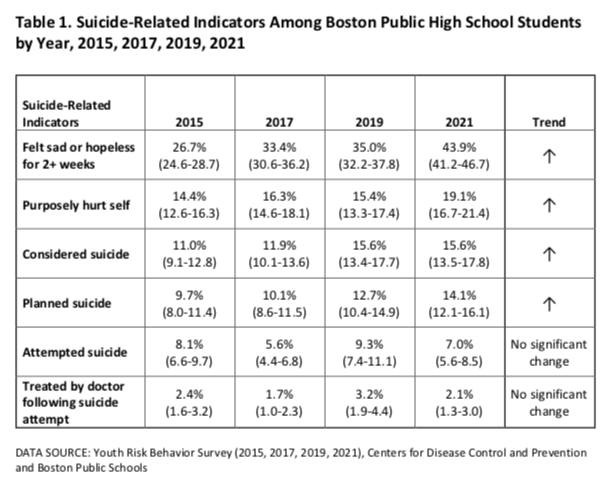

Dr. Bisola Ojikutu, commissioner of the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC), Ojikutu referenced a newly-published “Health of Boston’s Mental Health” report that shows more than 40 percent of BPS high school students report “persistent sadness and hopelessness.” She said an increasing number have considered, or even planned, suicide.

“I think we’re all aware that our youth are in crisis. They need our help more than ever before. According to our report released today, many young people in Boston are struggling with their mental health and well-being.”

Roughly $17 million in funding comes from the federal American Rescue Plan (ARPA) aimed at mitigate problems associated with COVID-19, a source already approved by the City Council. The remaining money comes from a federal Department of Education grant, and a federal substance abuse grant.

“There is still so much work to be done on this front,” said Lee School principal Paul Kennedy. “During a short time, the Lee community has had multiple high-impact incidents highlighting the need for robust supports in our schools. These investments…will allow us to build a resilient community and empower our school social workers with the skills they need to support us in hard times in a trauma-informed manner.”

One program, the $2.5 million “Transforming Boston Access to Mental Health,” is a partnership with UMass Boston, which says it will recruit, retain, and place 263 university students into BPS schools, while also creating a pipeline of BPS students seeking out behavioral health careers at UMass Boston.

“The kids are not okay,” said UMass Boston Chancellor Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, “and we need to step up to get in front of a once in a century set of formations that have created such despair and such a sense of hopelessness that our doctors have so well-articulated.”

Suárez-Orozco added: “This project will address the growing need for mental health resources among our minority and marginalized youth, particularly addressing the…shortage of mental health providers with identities that reflect the lived experiences…that our students bring to our classrooms and our city day in and day out.”

Franciscan Children’s Hospital in Brighton will use another $2.5 million to expand a program that places mental health counselors and psychiatry services in BPS schools. The expansion will go to 10 new BPS sites, including Dorchester schools like the Lee School, the Jeremiah Burke High School, the Henderson K-12 Inclusion School, and Young Achievers School in Mattapan.

“As was said, the kids are not okay,” said Dr. Joseph Mitchell, noting that one in five children in the country suffer from anxiety and depression. “We are in the middle of an epidemic and we risk losing a generation of kids, but there is reason for optimism and hope.”

In her comments, Mayor Wu focused on the nuts and bolts of the programs – addressing the use of ARPA funds to stand up programs that will continue after the funding runs out, she said.

“This is a little bit unusual how Boston has used its federal recovery dollars,” she said. “In a lot of cities around the country it was used to plug holes or fill gaps temporarily. We’ve really been trying to show that more is possible…not just trying to do our best to put Band-Aids on the situations but build new infrastructure – demonstrate what works and what’s possible so we can keep moving forward.

“Boston sees critical infrastructure as not just roads and bridges…, but also as people, as mental health and the workforce that cares for those in need of these services,” she continued.

BPS Superintendent Mary Skipper said it will be essential in the coming months and the years ahead to have trusted professionals who kids can identify with in the schools.

“This will really mean that an additional 50,000 students will have direct service and it means we will begin building a core of an additional 300 that will come from university services for students and teachers,” Skipper said. “This collaboration will speak to training so many more professionals so that at days end they are here for our children, and that’s the best outcome we could ask for.”

The announcement piggybacked on the new BPHC report, which Dr. Ojikutu referred to several times in her comments. The report revealed data collected from students between 2015 and 2021 – a first look at primary source mental health data reflecting the pandemic years. In that report, more than 40 percent of BPS students reported feeling “persistent sadness and hopelessness” – which was up from 27 percent in 2015.

Additionally, an increasing number of students reported thinking about or planning suicide. Less than half of BPS students who felt this way reported accessing help.

Excluding substance abuse related visits, Roxbury had the highest number of Emergency Department visits for mental health issues. However, all of Dorchester’s zip codes were next (02121, 02122, 02124, and 02125), and Mattapan (02126) followed close behind. All were higher than the rest of Boston’s neighborhoods.

The data was startling for BPS students regarding race and ethnicity across the city, particularly for girls. According to the BPHC report, 8.4 percent of Black girls interviewed had attempted suicide, but only 1.3 percent were treated by a doctor afterward.

For Latinx girls, 9.7 percent interviewed had attempted suicide, and 3.5 percent were treated by a doctor afterwards. Some 51 percent of Latinx girls reported feeling sad or hopeless for more than two weeks, and 47.1 percent of Black females reported the same – far greater than any group of boys and Asian and White girls. Across the board, though, all girls interviewed appeared to be in much worse condition with mental health than boys in any category.

Interestingly, persistent anxiety issues were highest in Allston-Brighton, and lowest in West Roxbury – yet even throughout the rest of the city in the 20 percent range.

For those in the Lee School community, such as 8th grader Leihla Martinez and Parent Council member Lora Triplett, the news was welcomed as they have lived these mental health statistics in real time.

Martinez said her mother taught her not to judge a book by its cover when they encounter people with mental health challenges, and that many have gone through those challenges, and everyone needs someone to talk to. She said since she has been working with the Lee School social worker, her bottled up emotions have been freed, and she feels much better.

“Every day students come to school going through something that they don’t talk about,” she said. “Sometimes they don’t have anyone to talk to and sometimes they don’t feel safe to share with certain adults, so they just bottle it up inside. This can make us feel anger, anxiety, and can lead to depression. What we need is encouragement to share our story, and we need adults that make us feel safe and will listen when we talk about our challenges.”

Public Health, school leaders say they don’t regret pandemic school closings

The startling anecdotal reports and data included in the recent Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC) report on youth mental health appeared to show that existing problems were worsened by the pandemic, but city leaders stopped short of saying they regret closing city schools for nearly 18 months.

BPHC Commissioner Dr. Bisola Ojikutu (pictured here) noted youth mental health issues existed before COVID-19 but were “exacerbated” by the pandemic. Across the country and in Boston, many have pointed to the isolation and social arrested development brought on by long school closures, such as in Boston, for creating issues of anxiety, depression, and suicide.

Ojikutu on Wednesday said it was difficult to say if issues in the report were a result of the school closures or remote schooling.

“I think it’s a difficult question to answer,” she said. “I mean, we were certainly in the middle of an emergency, and I think decisions are always made in the middle of an emergency to address the needs at the time. What I can say is that during COVID-19 we all experienced senses of isolation, being removed from our normal social surroundings…and that has had an impact. It certainly had an impact on adults, and it had an impact on our children.”

She added there is a lot of work to do.

“This is going to have to continue for many years to come to make sure our children are mentally healthy and well,” she continued.

Supt. Mary Skipper added, on the question of school closures, that some issues now being seen could result from overuse of social media.

“I also think there are a lot of studies out there about social media impact on our young people and how much time they’re on social media and how social media can actually cause more isolation or negative feelings,” she said. “I think we’re to learn a lot more about this, but the good news is this is a huge step in behavioral health we have not had in a comprehensive way.”